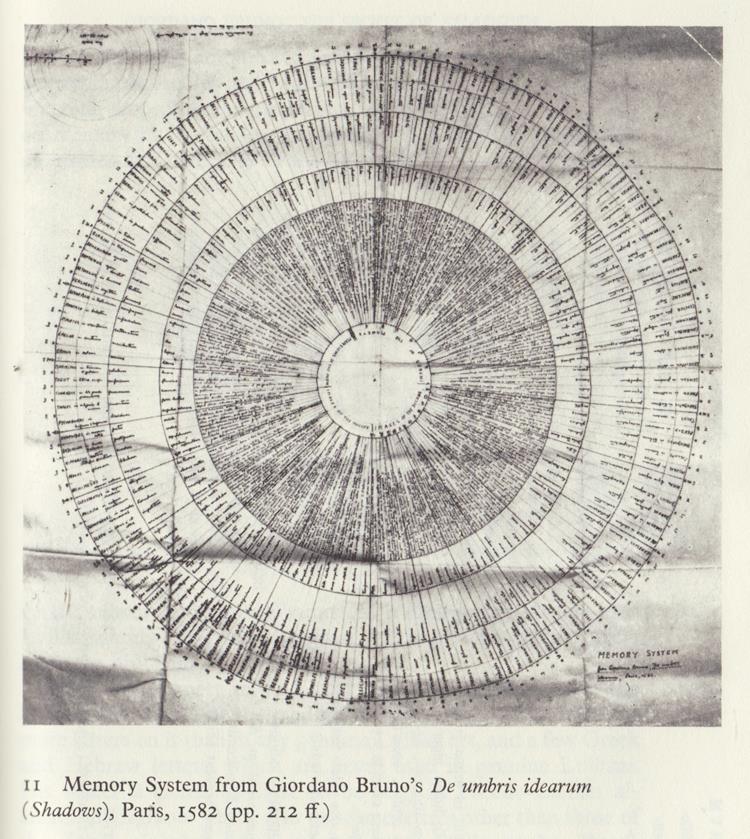

". . .But it is not enough to say vaguely that the memory wheels worked by magic. It was a highly systematized magic. Systematisation is one of the key-notes of Giordono Bruno's mind; there is a compulsion towards systems and systematisation in the magic mnemonics which drives their designer throughout his life to a perpetual search for the right system. . .Did he intend that there would be formed in the memory using these ever-changing combinations of astral images some kind of alchemy of the imagination, a philosopher's stone in the psyche through which every possible arrangement and combination of objects in the lower world--plants, animals, stones--would be perceived and remembered ? And that, in the forming and reforming of the astral images on the central wheel, the whole history of man would be remembered from above, as it were, all his discoveries, thoughts, philosophies, productions ?

Such a memory would be the memory of a divine man, of a Magus with divine powers through his imagination harnessed to the workings of cosmic powers. And such an attempt would rest on the Hermetic assumption that man's mind is divine, related in its origin to the star-governors of the world, able both to reflect and control the universe.

Magic assumes laws and forces running through the universe which the operator can use, once he knows the way to capture them. As I have emphasized in my other book, the Renaissance conception of an animistic universe, operated by magic, prepared the way for the conception of a mechanical universe, operated by mathematics. In this sense, Bruno's vision of an animistic universe of innumerable worlds through which run the same magico-mechanical laws, is a prefiguration, in magical terms, of the seventeenth-century vision. But Bruno's main interest was not in the outer world but in the inner world. And in his memory systems we see the effort to operate the magico-mechanical laws, not externally, but within, by reproducing in the psyche the magical mechanisms. The translation of this magical conception into mathematical terms has only been achieved in our own day. Bruno's assumption that the astral forces which govern the outer world also operate within, and can be reproduced or captured there to operate a magical-mechanical memory seems to bring one curiously close to the mind machine which is able to do so much of the work of the human brain by mechanical means.

Nevertheless, the approach from the mind machine angle does not really begin to explain Bruno's effort. From the Hermetic universe in which he lived the divine had not been banished. The astral forces were instruments of the divine; beyond the operative stars there were yet higher divine forms. And the highest form was, for Bruno, the One, the divine unity. The memory system aims at unification on the star level as a preparation for reaching the higher Unity. For Bruno, magic was not an end in itself but a means of reaching the One behind appearances. . . "

" . . .'I sat down under the shadow of him whom I desired.' One must sit under the shadow of the good and the true. To feel towards this through the interior senses, through the images in the human mind, is to sit under the shadow. There follow 'intentions' on light and darkness, and on the shadows which, descending from the supersubstantial unity proceed into an infinite multitude; they descend from the supersubstantial to its vestiges, images, and simulachra. Lower things are connected with higher and higher with lower; to the lyre of the universal Apollo there is a continual rising and falling through the chain of the elements. If the ancients knew a way by which memory, from the multitude of memorised species might reach unity, they did not teach it. All is in all in nature. So in the intellect all is in all. And memory can memorise all from all. The chaos of Anaxagoras is variety without order; we must put order into variety. By making the connections of the higher with the lower you have one beautiful animal, the world. The concord between higher and lower things is the golden chain from earth to heaven; as descent can be made from heaven to earth, so ascent may be made through this order from earth to heaven. The first intellect is the light of Amphitrite. This is diffused through all; it is the fountain of unity in which the innumerable is made one. The forms of deformed animals are beautiful in heaven; non-luminous metals shine in their planets; neither man, nor animals, nor metals are here as they are there. Illuminating, vivifying, uniting, conforming yourself to the superior agents you will advance in the conception and retention of the species. The light contains the first life, intelligence, unity, all species, perfect truths, numbers, grades of things. Thus what in nature is different, contrary diverse, is there the same, congruent, One. Try therefore with all your might to identify, co-ordinate, and unite the received species. Do not disturb your mind nor confuse your memory. Of all the forms of the world, the pre-eminent are the celestial forms. Through them you will arrive from the confused plurality of things at the unity. Parts of the body are better understood together than when taken separately. Thus when the parts of the universal species are not considered separately but in relation to their underlying order, what is there that we may not memorise, understand, and do ? One is the splendour of beauty in all. One is the brightness emitted from the multitude of species. The formation of things in the lower world is inferior to true form, a degradation and vestige of it. Ascend, then, to where the species are pure, and formed with true form. Everything that is, after the One, is necessarily multiplex and numerous. Thus on the lowest grade of the scale of nature is infinite number, on the highest is infinite unity. As the ideas are the principal forms of things, according to which all is formed, so we should form in us the shadows of ideas. We form them in us, as in the revolution of wheels. . . "

" . . .the unity of the All in the One is 'a most solid foundation for the truths and secrets of nature. For you must know that it is by one and the same ladder that nature descends to the production of things and the intellect ascends to the knowledgeof them; and that the one and the other proceeds from the unity and returns to unity, passing through the multitude of things in the middle.'

The aim of the memory system is to establish within, in the psyche, the return of the intellect to unity through the organisation of significant images. . . "

" . . .Thus the classical art of memory, in the truly extraordinary Renaissance and Hermetic transformation of it which we see in the memory system of Giordono Bruno has become the vehicle for the formation of the psyche of a Hermetic mystic and Magus. The Hermetic principle of reflection of the universe in the mind as a religious experience is organised through the art of memory into a magico-religious technique for grasping and unifying the world of appearances through arrangements of significant images. . . "

" . . .We saw that the magic of magic images could be interpreted in the Renaissance as an artistic magic; the image became endued with aesthetic power through being endowed with perfect proportions. We would expect to find that in a highly gifted nature, such as that of Giordano Bruno, the intensive inner training of the imagination in memory might take notable inner forms.

To painters and poets says Bruno, there is a distributed equal power. The painter excels in imaginative power (phantastica virtus); the poet excels in cogitative power to which he is impelled by an enthusiasm, deriving from a divine afflatus to give expression. Thus the source of the poet's power is close to that of the painter. ' Whence philosophers are in some ways painters and poets; painters are philosophers and poets. Whence true poets, true painters, and true philosophers seek one another out and admire one another. ' For there is no philosopher who does not mould and paint; whence that saying is not to be feared ' to understand is to speculate with images ', and the understanding ' either is the fantasy or does not exist without it '. . ."

" . . .'As the world is said to be the image of God, so Trismegistus does not fear to call man the image of the world '. Bruno's philosophy was the Hermetic philosophy; that man is the ' great miracle ' described in the Hermetic _Asclepius_; that his mind is divine, of a like nature with the star governors of the universe, as described in the Hermetic _Primander_. In _L'idea del theatro di Giulio Camillo_ we were able to trace in detail the basis in the Hermetic writings of Camillo's effort to construct a memory theatre reflecting ' the world ', to be reflected in ' the world ' of memory. Bruno works from the same Hermetic principles. If man's mind is divine, then the divine organisation of the universe is within it, and an art which reproduces the divine organisation in memory will tap the powers of the cosmos, which are in man himself.

When the contents of memory are unified there will begin to appear within the psyche ( so this Hermetic memory artist believes ) the vision of the One beyond the multiplicity of appearances. . ."

" . . .Since the divine mind is universally present in the world of nature, the process of coming to know the divine mind must be through the reflection of the images in the world of sense within the mind. Therefore the function of the imagination of ordering the images in memory is an absolutely vital one in the cognitive process. Vital and living images will reflect the vitality of life in the world, unifying the contents of memory and set up magical correspondencies between outer and inner worlds. Images must be charged with affects, and particularly with the affect of Love, for so they have the power to penetrate to the core both of the outer and the inner worlds--an extraordinary mingling here of classical memory advice on using emotionally charged images, combined with a magician's use of an emotionally charged imagination, combined again with mystical and religious use of love imagery. "

" . . .Bruno was undoubtedly genuinely trying to do something which he thought was possible, trying to find the arrangements of significant images which would work as a way of inner unification. The Art ' by which we may become joined to the soul of the world ' is one the guides in his religion. It is not a cloak under which to conceal that religion; it is an essential part of it, one of its main techniques.

Moreover, as we have seen, Bruno's memory efforts are not isolated phenomena. They belong into a definite tradition, the Renaissance occult tradition to which the art of memory in occult forms had been affiliated. With Bruno, the exercises in Hermetic mnemonics have become the spiritual exercises of a religion. And there is a certain grandeur in these efforts which represent, at bottom, a religious striving. The religion of Love and Magic is based on the Power of the Imagination, and on an Art of Imagery through which the Magus attempts to grasp, and hold within, the universe in all its ever changing forms, through images passing into the other in intricate associative orders, reflecting the ever changing movements of the heavens, charged with emotional affects, unifying, forever attempting to unify, to reflect the great monas of the world in its image, the mind of man. There is surely something which commands respect in an attempt so vast in its scope. . . "

". . .( Bruno ) has to the full the Renaissance creative power. He creates inwardly the vast forms of his cosmic imagination, and when he externalizes these forms in literary creation, works of genius spring to life. Had he externalized in art the statues which he moulds in memory, or the magnificent fresco of the images of the constellations which he paints in _Spaccio Della Bestia Trionfante_, a great artist would have appeared. But it was Bruno's mission to paint and mould within, to teach that the artist, the poet, and philosopher are all one, for the Mother of the Muses is Memory. Nothing comes out but what has been formed within, and it is therefore within that the significant work is done.

We can see that the tremendous force of image-forming which he teaches in the arts of memory is relevant to Renaissance imaginative creative force. But what of the frightful detail with which he expound those arts, the revolving wheels of the _Shadows_ system charged, not in general but in detail, with the contents of the worlds of nature and of man, or even more appalling accumulations of memory rooms in the system in _Images_? Are these systems erected solely as vehicles for passing on codes or rituals of a secret society? or, if Bruno really believed in them, surely they are the work of a madman?

There is undoubtedly, I think, a pathological element in the compulsion for system-forming which is one of Bruno's leading characteristics. But what an intense striving after method there is in this madness! Bruno's memory magic is not the lazy magic of the _Ars Notoria_, the practitioner of which just stares at a magical *nota* whilst reciting magical prayers. With untiring industry he adds wheels to wheels, piles memory rooms on memory rooms. With endless toil he forms the innumerable images which are to stock the systems ; endless are the systematic possibilities and they must all be tried. There is in all this what can only be described as a scientific element, a presage on the occult plane of the preoccupation with method of the next century.

For if Memory was the Mother of the Muses, she was also to be the Mother of Method. . . "

" . . .After some of the usual definitions of artificial memory, (Robert) Fludd devotes a chapter to explaining the distinction which he makes between two different types of art, which he calls respectively the 'round art (ars rotunda)', and the 'square art (ars quadrata). . . '

' . . .For the complete perfection of the art of memory the fantasy is operated in two ways. The first way is through *ideas*, which are forms separated from corporeal things, such as spirits, shadows (umbrae), souls and so on, also angels, which we chiefly use in our ars rotunda. We do not use this word 'ideas' in the same way that Plato does, who is accustomed to use it of the mind of God, but for anything which is not composed of the four elements, that is to say for things spiritual and simple conceived in the imagination; for example angels, demons, the effigies of stars, the images of gods and goddesses to whom celestial powers are attributed and which partake more of a spiritual than a corporeal nature; similarly virtues and vices conceived in the imagination and made into shadows, which were also held as demons. '

The 'round art', then, uses magicised or talismanic images, effigies of the stars; 'statues' of gods and goddesses animated with celestial influences; images of virtues and vices, as in the old medieval art, but now thought of as containing 'demonic' or magical power. Fludd is working at a classification of images into potent and less potent such as was Bruno's constant preoccupation.

The 'square art' uses images of corporeal things, of men, of animals, of inanimate objects. When its images are of men or of animals, these are active, engaged in actions of some kind. These two arts, the round and the square, are the only two possible arts of memory, states Fludd.

'Memory can only be artificially improved, either by medicaments, or by the operation of the fantasy towards *ideas* in the round art, or through images of corporeal things in the square art. . . ' "

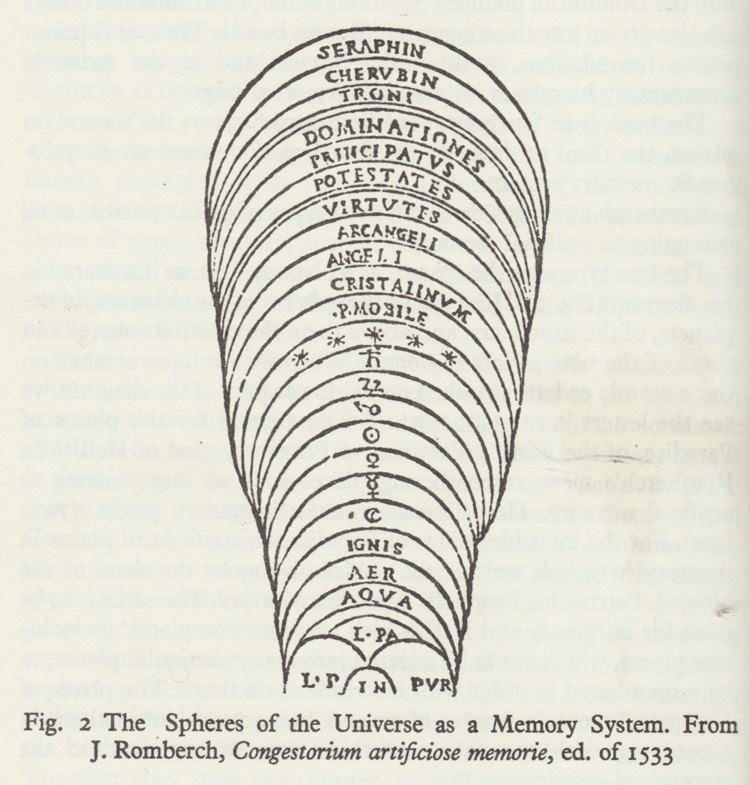

" . . .Having laid down the distinction between the *ars rotunda* and the *ars quadrata* and the different kinds of images to be used in each, and having made clear his view that the *ars quadrata* must always use real buildings, Fludd now arrives at the exposition of his memory system. This is a combination of the round and the square. Based on the round heavens, the zodiac and the spheres of planets, it uses in combination with these, buildings which are to be placed in the heavens, buildings containing places with memory images on them which will be, as it were, astrally activated by being organically related to the stars.

. . .

The striking and exciting feature of Fludd's memory system is that the memory buildings which are to be placed in the heavens in this new combination of the round and the square arts, are what he calls 'theatres'. And by this word 'theatre' he does not mean what we should call a theatre, a building consisting of a stage and an auditorium. He means a stage.

' I call a theatre (a place which) all actions of words, of sentences, of particulars of speech or of subjects are shown, as in a public theatre in which comedies and tragedies are acted. . . "

" . . .In his third book on temples, Vitruvius describes how the figure of man with extended arms and legs fits exactly into a square or a circle. In the Italian Renaissance, this Vitruvian image of Man within the square or circle became the favourite expression of the relation of the microcosm to the macrocosm, or, as Rudolf Wittkower puts it, 'invigorated by the Christian belief that Man as the image of God embodied the harmonies of the Universe, the Vitruvian figure inscribed in a square and a circle became a symbol of the mathematical sympathy between microcosm and macrocosm. How could the relation of Man to God be better expressed. . .than by building the house of God in accordance with the fundamental geometry of square and circle ?' This was the preoccupation of all the great Renaissance architects. . ."

" . . .It is a curious and significant fact that the art of memory is known and discussed in the seventeenth century not only, as we should expect, by a writer like Robert Fludd who is still following the Renaissance tradition, but also by the thinkers who are turning in the new directions, by Francis Bacon, by Descartes, by Leibniz. For in this century the art of memory underwent yet another of its transformations, turning from a method of memorising the encyclopaedia of knowledge, of reflecting the world in memory, to an aid for investigating the encyclopaedia and the world with the object of discovering new knowledge. It is fascinating to watch how, in the trends of the new century, the art of memory survives as a factor in the growth of scientific memory. . . "

" . . .Francis Bacon had a very full knowledge of the art of memory and himself used it. The importance with Bacon attached to the art of memory is shown by the fact that it figures quite prominently in the _Advancement of Learning_ as one of the arts and sciences which are in need of reform, both in their methods and in the ends for which they are used. The extant art of memory could be improved, says Bacon, and it should be used, not for empty ostentation, but for useful purposes. The general trend of the _Advancement_ towards improving thearts and sciences and turning them to useful ends is brought to bear on memory, of which, says Bacon, there is an art extant 'but it seemeth to me that there are better precepts than that art, and better practices of that art than those received'. As now used the art may be 'raisedto points of ostentation prodigious' but it is barren, and not used for serious 'business and occasions'. He defines the art as based on 'prenotions' and 'emblems', the Baconian version of places and images :

'This art of memory is but built upon two intentions; the one prenotion, the other emblem. Prenotion discargeth the indefinite seeking of that we would remember, and directeth us to seek in a narrow compass, that is, somewhat that hath congruity with our place of memory. Emblem reduceth conceits intellectual to images sensible, which strike the memory more; out of which axioms may be drawn better practique than that in use. . .'

Places are further defined in the _Novum Organum_ as the

'order or distribution of Common Places in the artificial memory, which may be either Places in the proper sense of the word, as a door, a corner, a window, and the like; or familiar and well known persons; or anything we choose (provided they are arranged in a certain order), as animals, herbs; also words, letters, characters, historical personages. . .'

Such a definition as this of different types of places comes straight out of the mnemonic text-books.

The definition of images as 'emblems' is expanded in the _De Augmentis Scientiarum_ :

'Emblems bring down intellectual to sensible things; for what is sensible always strikes the memory stronger, and sooner impresses itself than the intellectual. . .And therefore it is easier to retain the image of a sportsman hunting the hare, of an apothecary ranging his boxes, an orator making a speech, a boy repeating verses, or a player acting his part, than the corresponding notions of invention, disposition, elocution, memory, action.'

Which shows that Bacon fully subscribed to the ancient view that the active image impresses itself best on memory, and to the Thomist view that intellectual things are best remembered through sensible things. . . "

" . . .It was therefore roughly speaking the normal art of memory using places and images which Bacon accepted and practised. How he proposed to improve it is not clear. But amongst the new uses to which it was to be put was the memorising of matters in order so as to hold in the mind for investigation. This would help scientific enquiry, for by drawing particulars out of the mass of natural history, and ranging them in order, the judgement could be more easily brought to bear upon them. Here the art of memory is being used for the investigation of natural science, and its principles of order and arrangement are turning into something like classification.

The art of memory has here indeed reformed from 'ostentatious' uses by rhetoricians bent on impressing by their wonderful memories and turned to serious business. And amongst the ostentatious' uses which are to be abolished in the reformed use of the art Bacon certainly has in mind the occult memories of the Magi. 'The ancient opinion that man was a microcosmus, an abstract or model of the world, hath been fantastically strained by Paracelsus and the alchemists', he says in _Advancement_. It was on that opinion that 'Metrodorian' memory systems such as that of Fludd were based. To Bacon such schemes might well have seemed 'enchanted glasses' full of distorting 'idola', and far from that humble approach to nature in observation and experiment which he advocated. . ."

" . . .Descartes also exercised his great mind on the art of memory and how it might be reformed, and the mnemonic author who gave rise to his reflections was none other than Lambert Schenkel. In the _Cogitationes Privatae_ there is the following remark :

'On reading through Schenkel's profitable trifles (in the book _De Art Memoria_) I thought of an easy way of making myself master of all I discovered through the imagination. This would be done through the reduction of things to their causes. Since all can be reduced to one it is obviously not necessary to remember all the sciences. When one understands the causes all vanished images can easily be found again in the brain through the impression of the cause. This is the true art of memory and it is plain contrary to his (Schenkel's) nebulous notions. Not that his (art) is without effect, but it occupies the whole space with too many things and not in the right order. The right order is that the images should be formed in dependence on one another. He (Schenkel) omits this which is the key to the whole mystery.

I have thought of another way; that out of unconnected images should be composed new images common to them all, or that one image should be made which should have reference not only to the one nearest to it but to them all -- so that the fifth should refer to the first through a spear thrown on the ground, the middle one through a ladder on which they descend, the second one through an arrow thrown at it, and similarly the third should be connected in some way either real or fictitious.'

Curiously enough, Descarte's suggested reform of memory is nearer to 'occult' principles than Bacon's, for occult memory does reduce all things to their supposed causes whose images when impressed on memory are believed to organise the subsidiary images. The phrase about the 'impression of the cause' through which all vanished images can be found might easily be that of an occult memory artist. Of course Descartes is certainly not thinking on such lines but his brilliant new idea of organising memory on causes sounds curiously like a rationalisation of occult memory. His other notions about forming connected images are far from new and can be found in some form in nearly every text-book.

It seems unlikely that Descartes made much use of local memory which he neglected to practise much in his retreat and which he regarded as 'corporeal memory' and 'outside of us' as compared with 'intellectual memory' which is within and incapable of increase or decrease. This singularly crude idea is in keeping with Descarte's lack of interest in the imagination and its functioning. . . "

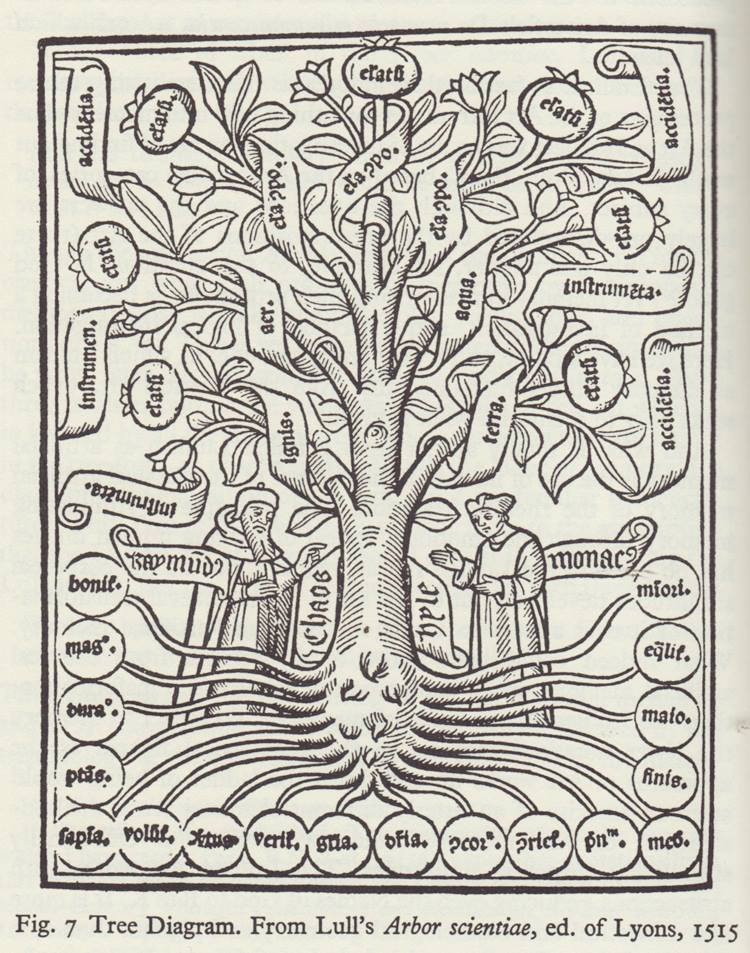

" . . .Both Bacon and Descartes knew of the art of (Ramon) Lull to which they both refer in very derogatory terms. . .Thus neither the discoverer of the inductive method, which was not to lead to scientifically valuable results, nor the discoverer of the method of analytical geometry, which was to revolutionise the world as the first systematic application of mathematics to the investigation of nature, have anything good to say of the method of Ramon Lull. Why indeed should they? What possible connection can there be between the 'emergence of modern science' and that mediaeval art, so frantically revived and 'occultised' in the Renaissance, with its combinatory systems based on Divine Names or attributes. Nevertheless the Art of Ramon Lull had this in common with the aims of Bacon and Descartes. It promised to provide a universal art or method which, because based on reality, could be applied for the solution of all problems. Moreover it was a kind of geometrical logic, with its squares and triangles and its revolving combinatory wheels; and it used a notation of letters to express the concepts with which it was dealing.

. . .Descartes said that what he was meditating was not an *ars brevis* of Lull, but a new science which would be able to solve all questions concerning quantity. The operative word is, of course, 'quantity', making the great change from qualitative and symbolic use of number. The mathematical method was hit upon at last, but in order to realise the atmosphere in which it was found we should know something of those frenzied pre-occupations with arts of memory, combinatory arts, Cabalist arts, which the Renaissance bequeathed to the seventeenth century. The occultist tide was receding and in the changed atmosphere the search turns in the direction of the rational method. . ."

" . . .Another interesting example of the emergence of a more rational method from Renaissance occultism is afforded by the _Orbis Pictus_ of Comenius (first edition in 1658). This was a primer for teaching children languages, such as Latin, German, Italian, French, by means of pictures. The pictures are arranged in the order of the world, pictures of the heavens, the stars and celestial phenomena, of animals, birds, stones and so on, of man and all his activities. Looking at the picture of the sun, the child learned the word for sun in all the different languages; or looking at the picture of a theatre, the word for theatre in all the languages. This may seem ordinary enough now that the market is saturated with children's picture books, but it was an astonishingly original pedagogic method in those times and must have made language-learning enjoyable for many a seventeenth-century child as compared to the dull drudgery accompanied by frequent beatings of traditional education.

Now there can be no doubt that the _Orbis Pictus_ came straight out of Campanella's _City of the Sun_, that Utopia of astral magic in which the round central sun temple, painted with the images of the stars, was surrounded by the concentric circles of the walls of the city on which the whole world of the creation and of man and his activities was represented in images dependent on the central causal images. As has been said earlier, the _City of the Sun_ could be used as an occult memory system through which everything could be quickly learned, using the world 'as a book' and as 'local memory'. The children of the Sun City were instructed by the Solarian priests who took them round the City to look at the pictures, whereby they learned the alphabets of all languages and everything else through the images on the walls. The pedagogic method of the highly occult Solarians, and the whole plan of their City and its images, was a form of local memory, with its places and images. Translated into the _Orbis Pictus_, the Solarian magic memory system becomes a perfectly rational, and extremely original and valuable, language primer. . . "

" . . .One of the pre-occupations of the seventeenth-century was the search for a universal language. Stimulated by Bacon's demand for 'real characters' for expressing notions -- characters or signs which should really in contact with the notions they expressed -- Comenius worked in this direction and through his influence a whole group of writers laboured to found universal languages on 'real characters'. As has been shown, these efforts come straight out of the memory tradition with its search for signs and symbols to use as memory images. The universal languages are thought of as aids to memory and in many cases their authors are obviously drawing on the memory treatises. And it may be added that the search for 'real characters' comes out of the memory tradition on its occult side. The seventeenth-century universal language enthusiasts are translating into rational terms efforts such as those of Giordano Bruno to found universal memory systems on magic images which he thought of as directly in contact with reality.

Thus the Renaissance methods and aims merge into seventeenth-century methods and aims and the seventeenth-century reader did not distinguish the modern aspects of the age so sharply as we do. For him, the methods of Bacon or of Descartes were just two more of such things. . . "

" . . .But it is Leibniz who affords by far the most remarkable example of the survival of influences from the art of memory and from Lullism in the mind of a great seventeenth-century figure. It is, of course, generally known that Leibniz was interested in Lullism and wrote a work _De Arte Combinatoria_ based on adaptations of Lullism. What is not well known, is that Leibniz was also very familiar with the traditions of the classical art of memory. In fact, Leibniz's efforts at inventing a universal calculus using combinations of significant signs or characters can undoubtedly be seen as descending historically from Renaissance efforts to combine Lullism with the art of memory of which Giorano Bruno was such an outstanding example. But the significant signs or characters of Leibniz's 'characteristica' were mathematical symbols, and their logical combinations were to produce the invention of the infinitesimal calculus.

Amongst Leibniz's unpublished and published works there are many references to the art of memory. . .*Mnemonica*, says Leibniz, provides the matter of an argument; *Methodologia* gives it form; and *Logica* is the application of the matter to the form. He then defines *Mnemonica* as the joining of the image of some sensible thing to the thing to be remembered, and this image he calls *nota*. The 'sensible' *nota* must have some connection with the thing to be remembered, either because it is like it, or unlike it, or connected to it. In this way words can be remembered, though this is very difficult, and also things. Here the mind of the great Leibniz is moving on lines which takes us straight back to _Ad Herennium_, on images for things, and the harder images for words; he is also recalling the three Aristotelian laws of association so intimately bound up with the memory tradition of the scholastics. He then mentions that things seen are better remembered than things heard, which is why we use *notae* in memory, and adds that the hieroglyphs of the Egyptians and the Chinese are in the nature of memory images. He indicates 'rules for places' in the remark that the distribution of things in cells or places is helpful for memory. . .

. . .Thus Leibniz knew the memory tradition extremely well; he had studied the memory treatises and had picked up, not only the main lines of the classical rules, but also complications which had grown up around these in the memory tradition. And he was interested in the principles on which the classical art was based.

Of Leibniz and Lullism much has been written, and ample evidence of the influence upon him of the Lullist tradition is afforded by the _Dissertatio de Arte Combinatoria_ (1666). The opening diagram in this work, in which the square of the four elements is associated with the logical square of opposition, show his grasp of Lullism as a natural logic. Leibniz interprets Lullism with arithmetic and with the 'inventive logic' which Francis bacon wanted to improve. There is already here the idea of using the 'combinatoria' with mathematics. . .In this new mathematical-Lullist art, says Leibniz, *notae* will be used as an alphabet. These *notae* are to be as 'natural' as possible, a universal writing. They may be like geometrical figures, or like the 'pictures' used by the Egyptians and the Chinese, though the new Leibniziam *notae* will be better for 'memory' than these. It is perfectly clear that Leibniz is emerging out of a Renaissance tradition -- out of those unending efforts to combine Lullism with the classical art of memory. . . "

" . . .As is well known, Leibniz formed a project known as the 'characteristica'. Lists were drawn up of all the essential notions of thought, and to these notions were to be assigned symbols or 'characters'. The influence of the age-long search since Simonides, for 'images for things' on such a scheme is obvious. Leibniz knew of the aspirations so widely current in the time for the formation of a universal language of signs and symbols, but such schemes, as has already been mentioned, were themselves influenced by the mnemonic tradition. And the 'characteristica' of Leibniz was to be more than a universal language; it was to be a 'calculus'. The 'characters' were to be used in logical combinations to form a universal art or calculus for the solution of all problems. The mature Leibniz, the supreme mathematician and logician, is obviously still emerging straight out of Renaissance efforts for conflating the classical art of memory with Lullism by using the images of the classical art on Lullian combinatory wheels.

Allied to the 'characteristica' or calculus in Leibniz's mind was the project for an encyclopaedia which was to bring together all the arts and sciences known to man. When all knowledge was systematised in the encyclopaedia, 'characters' could be assigned to all notions, and the universal calculus would eventually be established for the solution of all problems. Even religious difficulties would be removed by it.

Ramon Lull believed that his Art, with its letter notations and revolving geometrical figures, could be applied to all subjects of the encyclopaedia, and that it could convince Jews and Mohammedans of the truths of Christianity. Giulio Camillo had formed a Memory Theatre in which all knowledge was to be synthesised through images. Giordano Bruno, putting the images in movement on the Lullian combinatory wheels, had travelled all over Europe with his fantastic arts of memory. Leibniz is the seventeenth-century heir to this tradition. . . "

" . . .Let us turn back now and gaze once more at that strange diagram which we excavated from Bruno's _Shadows_, where the magic images of the stars revolving on the central wheel control the images on other wheels of the contents of the elemental world and the images on the outer wheel representing all the activities of man. Or let us remember _Seals_ where every conceivable memory method known to the ex-Dominican memory expert is tirelessly tried in combinations the efficacy of which rests on the memory image conceived of as having magical force. Let us read again the passage at the end of _Seals_ in which the occult memory artist lists the kinds of images which may be used on the Lullian combinatory wheels, amongst which figure prominently signs, *notae*, characters, seals. Or let us contemplate the spectacle of the statues of gods and goddesses, assimilated to the stars, revolving both as magic images of reality and as memory images comprehending all possible notions, on the wheel in _Statues_. Or think of the inextricable maze of memory rooms in _Images_, full of images of all things in the elemental world, controlled by the significant images of the Olympian gods.

This madness had a very complex method to it, and what was its object? To arrive at universal knowledge through combining significant images of reality. Always we had the sense that there was a fierce scientific impulse in those efforts, a striving, on the Hermetic plane, after some method of the future, half-glimpsed, half-dreamed of, prophetically foreshadowed in those infinitely intricate gropings after a calculus of memory images, after arrangements of memory orders in which the Lullian principle of movement should somehow be combined with a magicised mnemonics using characters of reality.

Looking back now from the vantage point of Leibniz we may see Giordano Bruno as a Renaissance prophet, on the Hermetic plane, of scientific method, and a prophet who shows us the importance of the classical art of memory, combined with Lullism, in preparing the way for the finding of a Great Key. . . "

" . . .But the matter does not end here. We have always hinted or guessed that there was a secret side to Bruno's memory systems, that they were a mode of transmitting a religion, or an ethic, or some message of universal import. And there was a message of universal love and brotherhood, of religious toleration, of charity and benevolence implied in Leibniz's projects for his universal calculus or characteristic. Plans for the reunion of the churches, for the pacification of sectarian differences, for the foundation of an 'Order of Charity', form a basic part of his schemes. The progress of the sciences, Leibniz believed, would lead to an extended knowledge of the universe, and therefore a wider knowledge of God, its creator, and thence to a wider extension of charity, the source of all virtues. Mysticism and philanthropy are bound up with the encyclopaedia and the universal calculus. When we think of this side of Leibniz, the comparison with Bruno is again striking. The religion of Love, Art, Magic, and Mathesis was hidden in the Seals of Memory. A religion of love and general philanthropy is to be made manifest, or brought about, through the universal calculus. If we delete Magic, substitute genuine mathematics for Mathesis, understand Art as the calculus, and retain Love, the Leibnizian aspirations seem to approximate strikingly closely -- though in a seventeenth-century transformation -- to those of Bruno. . . "

". . . The art of memory is a clear case of a marginal subject, not recognised as belonging to any of the normal disciplines, having been omitted because it was no one's business. And yet it has turned out to be, in a sense, everyone's business. The history of the organisation of memory touches at vital points on the history of religion and ethics, of philosophy and psychology, of art and literature, of scientific method. When we reflect on these profound affiliations of our theme it begins to seem after all not so surprising that the pursuit of it should have opened up new views of some of the greatest manifestations of our culture. . . "